A Message from Joanne Conroy, Woman of Impact and CEO of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health

More American women are dying of pregnancy-related complications in the U.S. than any other developed country. The rate of women who die during or after childbirth has been rising here in spite of a global downward trend elsewhere. From 2011 to 2015, more than 4,000 maternal deaths occurred in the U.S. I asked Dr. Liz Erekson, who is our interim chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology, to help shed some light on this topic.

If we are really concerned about health of communities, this should bother us!

More American women are dying of pregnancy-related complications in the U.S. than any other developed country. The rate of women who die during or after childbirth has been rising here in spite of a global downward trend elsewhere. From 2011 to 2015, more than 4,000 maternal deaths occurred in the U.S. I asked Dr. Liz Erekson, who is our interim chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology, to help shed some light on this topic.

By the way, Liz for the past year has been leading this service, which was recently recognized by U.S News & World Report in the top 50 list for Gynecology. She was incredibly helpful in crafting this journal piece about maternal mortality to increase awareness. Liz emphasized that every maternal death touches obstetric providers to their core.

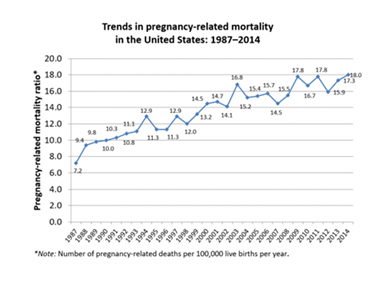

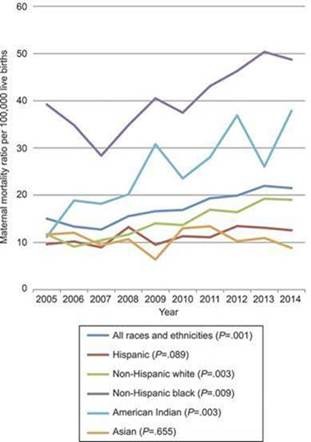

Over the last 15 years, we have seen a 26 percent increase in maternal mortality in the United States —18.8 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014. Unfortunately, these rates also reflect a great disparity in care with heart failure and pregnancy-related hypertension disproportionately impacting black women. These rates and other statistics on maternal mortality can be found on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website linked here.

Also below are two graphs depicting trends in maternal mortality (maternal deaths/100,000 live births) and by ethnic group and race. These were published in Obstetrics and Gynecology, which is the official publication for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Tennis star Serena Williams is a very public example. She shared her agonizing postnatal experience that demonstrated neither income nor education level make women immune from these complications. According to a New York Times article about her ordeal, hospital employees did not act on her concern that she was experiencing a pulmonary embolism, which is a sudden blockage of an artery in the lung caused by a blood clot. She is prone to such clots, a condition that nearly killed her in 2011. The day after giving birth to her daughter via cesarean section, she was having trouble breathing and immediately assumed she was having another pulmonary embolism. She alerted a nurse and asked for a CT scan and a blood thinner, but the nurse suggested that pain medication had perhaps left her confused. Later that day, a CT scan showed several clots in her lungs, but the clots were only the beginning of her complications. In the days after she gave birth, she required two additional return trips to the operating room and countless other medical interventions. Serena's story has a happy ending of recovery and healing for both her and her family.

As of 2018, New Hampshire ranked 19th among the others states for maternal mortality with 16.8 deaths per 100,000 live births. This is according to the America's Health Rankings website, which is published by the United Health Foundation, linked here.

New Hampshire's two biggest issues are rural obstetric care delivery and opioid use disorder among pregnant women. In New Hampshire, maternal mortality statistics are tracked with the state of New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services through the Northern New England Perinatal Quality Improvement Network (NNEPQIN). NNEPQIN was founded at Dartmouth-Hitchcock over 13 years ago to provide a reasonable framework to help rural obstetric care hospitals continue to safely offer trial of labor for women after prior cesarean delivery (TOLAC). When NNEPQIN was founded by Michele Lauria, MD, who was one of our maternal fetal medicine physicians and is now at Eastern Maine Healthcare, and current D-H clinicians Emily Baker, MD, Division Director for Maternal Fetal Medicine and Vice Chair for Obstetrics, Vicki Flanagan, RN, Perinatal Outreach Educator, and Maggie Minnock, Director of Regional Program for Women's & Children's Health at CHaD, we had 28 hospitals in the state of New Hampshire offering inpatient obstetrical services. Today, we have only 16.

The delivery of rural obstetric care across our country is a real issue…one we feel acutely here in New Hampshire due to our rural location. Recent studies in the Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) highlight that the closure of inpatient obstetrical services in a county actually increase the out-of-hospital deliveries and the number of deliveries in hospitals that have no obstetrics services. Even more concerning are the recent reports that even after adjusting for maternal age, race/ethnicity and education, the closure of obstetrical facilities increases pre-maturity (preterm deliveries) by 0.67 percent in the first year after the loss of these services. Given that 20 percent of U.S. families live in a rural county, this is a significant issue we will be struggling with for years to come. Here are links to two JAMA articles that are worth reading on this topic: Eroding Access and Quality of Childbirth Care in Rural U.S. Counties and Association Between Loss of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services and Birth Outcomes in Rural Counties in the United States . This isn't a new topic for Dartmouth-Hitchcock. We were talking about this in a JAMA article in 1979.

Our other big issue in New Hampshire is access to mental health services, including the treatment of opioid use disorder among pregnant women. The prevalence of mothers delivering who are suffering from opioid use disorder (either in-treatment or without treatment) is 8 to 12 percent across different hospitals in the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health system. Our efforts surrounding optimal treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy continue. In 2017, we introduced throughout the system universal screenings (SBIRT—screening, brief intervention, referral to treatment) in all pregnant patients twice throughout their pregnancy — once at the initial pregnancy visit and once in the third trimester. Through the dedicated efforts of many across the entire OB/GYN service line, SBIRT is now happening at all our locations that deliver prenatal care. In February 2018, Dartmouth-Hitchcock, led by Dr. Julia Frew, received a $2.7 million federal grant to implement better access and treatment for pregnant women suffering from opioid use disorder across 7 different outpatient prenatal care locations in the state. For more on that story, click here.

Progress

Despite these grim statistics, there is substantial progress being made. By implementing pathways and checklists for things like obstetric hemorrhage and pre-eclampsia, some states, like California, have succeeded in reducing maternal mortality (see graph below published in Obstetrics and Gynecology). We, in New Hampshire, do this collaboratively through the efforts of NNEPQIN.

Unadjusted combined maternal and late maternal mortality rates, California, 2000–2014. Includes pregnancy-related deaths occurring within 1 year of pregnancy. California revised their death certificate in 2003 to a nonstandard question that asks about deaths within 1 year of pregnancy. Before 2003, California did not have a pregnancy question on their death certificate.

What can we advocate for?- Education for both health care providers and the patients we serve

Women need to educate themselves. Pre-existing conditions, lack of insurance, Hispanic or African-American race, statistically place women at higher risk for a pregnancy-related complications. Knowing the specific issues our patients face in New Hampshire surrounding rural access to care and mental illness/substance use disorder will help us direct attention and resources to things that can help.

- Communication & public knowledge around the reasons

Women now face more chronic health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and heart disease in pregnancy. Celebrating the birth process as a normal physiologic event and encouraging vaginal delivery will help avoid the complications and morbidity of repeat cesarean sections, which put mothers at greater risk for life-threatening complications.

- Advocate for access

Advocating to increase women's access to health insurance in the first year post-partum instead of just the first six weeks to make sure that mothers and their families have health care they need.

- Valuing the team

Valuing women's centered care through support of integrated and collaborative obstetric care teams that include physicians, midwives, social workers, community health resource workers, behavioral health interventionist, care managers, nurses, lactation experts, doulas and many others…It truly takes a village.

- Important legislative efforts at the federal level to help combat this issue

Support the development of state Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs) in every state through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): H.R. 1318, a bipartisan bill introduced by Representatives Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-WA), Diana DeGette (D-CO), and Ryan Costello (R-PA), and S. 1112, a bipartisan bill introduced by Senators Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND), and Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV).

A newer bill, but one that expands a lot of services for pregnant women, is the MOMMIES Act (Maximizing Outcomes for Moms through Medicaid Improvement and Enhancement of Services), which was introduced by U.S. Senators Cory Booker (D-NJ), Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), Tammy Baldwin (D-WI), Ben Cardin (D-MD), Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) and Kamala Harris (D-CA). The goal of this bill is to reduce the United States' rising maternal mortality rates, improve maternal and infant health outcomes, and close the disparities that continue to put mothers and children of color at risk by enhancing coverage for pregnant women covered by Medicaid.

Stories such as Serena's bring into focus what's happening to thousands of women around the United States. Maternal mortality can strike any pregnant woman (or post pregnancy) at anytime, anywhere. Your fame, your education, your income level—none of those ultimately can protect you. And so we have to prepare everyone for those circumstances. As health care providers, we need to educate and prepare mothers to celebrate the normal physiologic event of pregnancy, while being aware of potential health risks during and after their pregnancy so they can advocate for their health.